Culture

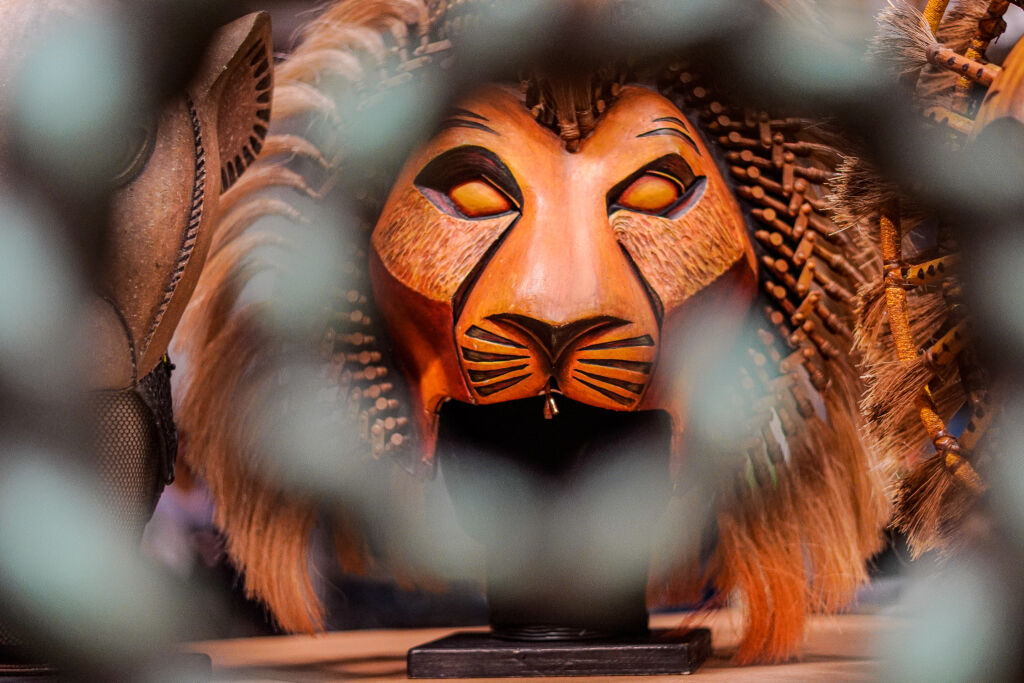

"The Lion King." Photo by Andrew J. Williams III.

"The Lion King." Photo by Andrew J. Williams III.

Inside the World of “The Lion King,” at the Kennedy Center from July 11-29

July 6, 2023 @ 1:00pm

Take a peek behind the scenes to learn about the inner workings of puppetry for the highest-grossing musical of all time.

I’d been to the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to see several notable theatre productions, including “Phantom of the Opera” and “Hamilton,” but never to hang out with puppets.

Michael Reilly is the puppet supervisor for Disney’s “The Lion King.” The production, currently playing at the Kennedy Center, is the world’s number-one musical and is on an impressive 26-year run (this is year 24 for Reilly) of bringing to life the iconic animated story.

Fray was offered a rare glimpse behind the curtain and an opportunity to learn about one of the most mysterious components of one of Broadway’s most celebrated and decorated shows.

For many Millenials, “Eureeka’s Castle,” “The Muppets,” “Fraggle Rock,” and “Sesame Street” hold a nostalgic place in our hearts. But kids don’t consider the inner workings of puppetry — perhaps that’s part of the magic. As an adult, I had a lot of questions.

But, Really, What’s a Puppeteer?

Michael Reilly. Photo by Andrew J. Williams III.

The first question was the most obvious one. “What is a puppeteer?”

“We have two different careers: puppeteer is one where you are literally acting with operating the puppets,” Reilly says. “It’s different on our show; I’m more of a puppet technician and in charge of making and maintaining the puppets and teaching (others) how to puppeteer.”

The puppets are invented by Julie Taymor, the award-winning director and writer who adapted “The Lion King” to the stage, and Michael Curry, the prestigious Oregon-based puppet designer whose accolades include the World Cup, Olympics, Disneyland, the Super Bowl, and Burning Man.

Reilly directs a three-person puppet department — a tiny shop, considering the scale of “The Lion King” and all its moving parts and players: 230 puppets and 49 cast members.

He and his team maintain a methodic schedule, arriving first thing in the morning to give principal puppets, like Mufasa and Scar, complete workups, before moving on to weeklies: puppets that are scheduled to get daily checks on a weekly basis, given the sheer number.

“A lot of work goes into the show before the actors enter the building,” Reilly says. “We’re like the little mice working behind the scenes.”

Finally, the team addresses the list of repairs made the previous night before pre-setting all the puppets two hours before the curtains rise.

The team is even on rare occasions tasked with modifying puppets to fit different body types when new actors join the production.

The World of Humans and Puppets

Reilly explains “The Lion King” is unique among contemporary productions. They don’t hire puppeteers; they hire actors, singers and dancers who are taught to be puppeteers and take the lead in animating the show’s signature creations. And humans aren’t hidden during performances. Instead, they usually wear black velvet body suits to keep the focus on the colorful puppets.

Michael Reilly. Photo by Andrew J. Williams III.

In “The Lion King,” each puppeteer operates between one and 14 different puppets, often handling multiple puppets in a single night.

“It takes a lot of work to become fluent in different puppetry styles,” Reilly says.

Some are worn on the head, others are on a rod, and then there are traditional shadow puppets. There’s a giraffe, which requires learning to walk on three-foot stilts, and a giant elephant that requires four puppeteers to operate,

The loveable warthog Pumba is among the most complicated puppets to operate. He is a full-body puppet standing eight feet tall and weighing 50 pounds. The puppeteer moves his arms to move the puppet’s tongue, eyes and nose, while his legs serve as the puppet’s front legs.

“All of those different parts are integral to [Pumba’s] performance,” Reilly explains.

Timon is a Bunraku puppet: a Japanese-Indonesian style of rod puppet with multiple manipulable features and limbs. Timon’s puppeteer is outfitted in green, representing the jungle, and Timon is fashioned in front of him.

“Puppeteers, actors, singers, dancers all come together in one amazing circle of life,” Reilly says in a sentimental nod to “The Lion King’s” opening song.

It’s also a poetic harmony between humans and puppets.

“We have the animals that are represented by the puppets and masks, but you also have the human, and you can play off that dichotomy. Sometimes Mufasa will take the mask off when he wants to talk to his son in a very human way. That’s the reason the show is a success; that’s the genius of The Lion King.”

African Roots

Photo by Andrew J. Williams III.

Taymor chose to pay homage to the animated movie’s African lineage through the fantastical, larger-than-life world she recreated for audiences.

Her choices are foundational to the puppets’ design and the musical’s ethos.

“Because it was a cartoon film, [the movie] didn’t have the opportunity to really dive down into, ‘What is ‘The Lion King?”” Reilly says. “’The Lion King’ is an African story. It’s so important for the theatre show to bring that back.”

Taymor’s adaption includes adding authentic South African music and integrating African references from the puppets and sets into the script. Several of the puppets are even partially constructed with baskets and other materials sourced from Africa.

“We do this song at the start of Act 2 called ‘One by One,’ which is this beautiful expression of joy; there are birds flying around, people singing and dancing, and in dashikis. It’s a wonderful representation of Africa.”

This musical number is one of only two scenes that don’t incorporate puppets, which, ironically, are among Reilly’s favorite moments in the musical.

“The Lion King” plays at the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts through July 29. Visit here to learn more about the show and pricing for tickets.

Kennedy Center for Performing Arts: 2700 F St. NW; kennedy-center.org // @kennedycenter

Want first access to select shows, exhibits and performances around the city? Join the District Fray community to access free and discounted tickets. Become a member and support local journalism today.