Culture

Photo: Delvinahair Productions

Photo: Delvinahair Productions

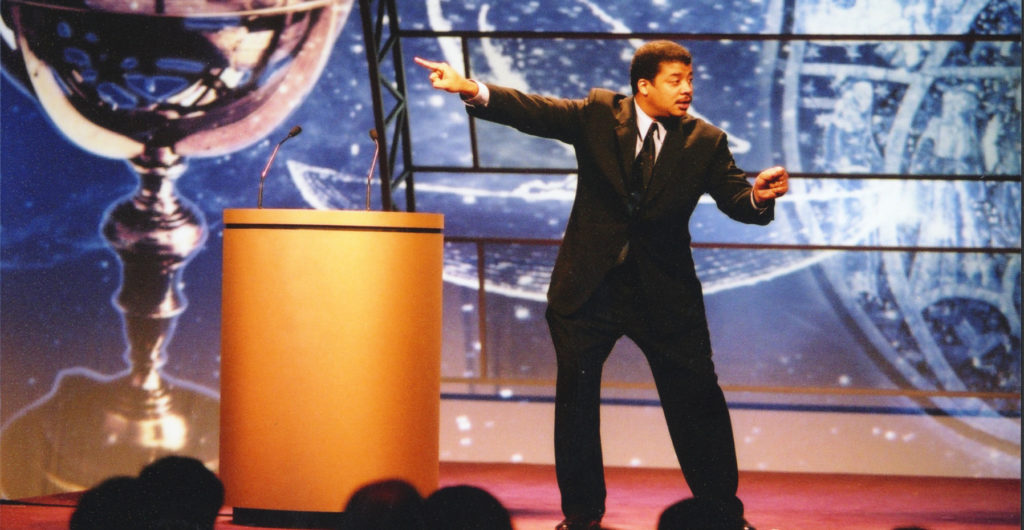

Letters to Tyson: Neil deGrasse Tyson Talks New Book, Twitter and Society’s Hunger for Science

October 4, 2019 @ 12:00am

“Do people write letters anymore? Not much.”

I’m sitting in an office phonebooth talking with arguably the most famous living scientist. At 60 years old, Neil deGrasse Tyson remembers the days when email and social media weren’t the most obvious vehicles for thoughtful discourse with people who followed his work. Instead, the best method was sitting in a room and typing or writing a letter.

“With letters, you get to pause and sit back and think about when someone sits down and composes a question, and they think that my life experience and expertise might illuminate a path they need to choose.”

Some letters required more from Tyson than others, forcing him to learn contextual foundations for which he’d root his answers in or making him dig deep into his own personal background to deliver a well-thought-out opinion, complete with humor and a personal vignette.

He’s been receiving letters for the better part of 30 years, keeping copies of ones he deems entertaining, thoughtful and worth revisiting. His latest book Letters from an Astrophysicist, hitting shelves on October 8, features 100 of his favorite letters – yet another opportunity to learn from one of the most renowned educators on the planet and perhaps in the universe.

With a book release comes a book tour, including a stop at Warner Theatre on October 23. Before reading Tyson’s collection of letters or hearing him speak live, read our conversation with the brilliant scientist.

On Tap: Do people still write letters? I feel like you could have just as easily made a book of your Twitter responses.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Do people write letters anymore? Not much. The communication channel tends to be Twitter and I’ve considered a Twitter book, but there’s no hurry for that. I put a lot of effort into my tweets, more than people think. I think long and hard to tweet, and it’s a big responsibility because I communicate with a lot of people – nearly 14 million people directly. A tweet triggers a neuron synapses snapshot of the collective brain, because I see people respond. If I say something funny and people laugh, then that works. And if they don’t, then I have to figure out why.

OT: How would you describe the book’s format?

NDT: The letters span a range of 30 years and most of them are from a specific 10-year span, and another set of letters are more open. For example, I wrote an open letter to my extended family and colleagues after I escaped lower Manhattan on 9/11 and was home and witnessed everything that had happened. I wrote a letter to NASA when I turned 60, and I compared and contrasted NASA and my own 60 years of life – that’s the opening of the book. I end the book with a letter to my father, but it’s a eulogy in the form of a letter. So, the book is bookended by letters – not individuals’ letters, but open letters. It’s a combination of all of the above.

OT: What about these letters stood out to you enough that you’d want to print them for readers?

NDT: This book is not, “Let me learn astrophysics,” and that’s not why these people have written to me. You get to share in their angst and see how a scientist and educator replies. Nearly every one of these letters probe people’s attitudes and beliefs and fears. Often scientists are associated with cold, meticulous content. You have to do that in the lab. But when you’re not in the lab, you have these human feelings too.

OT: What kind of letters made the cut? What about this selection proved to create a special narrative?

NDT: What I noticed was, some letters I invested more in my answers than others and it was because the person was coming from a place that deserved more attention than “Yes,” “No” or “Check out this website.” If it was more personal, more introspective, I would devote more energy to my replies. Then I’d finish and say, “You know, this has some good stuff in it.” So I kept a copy. I did that for about 15 or 20 years. There was 500 total that I kept in a folder. These are letters that had a little extra creative dimension to the replies. Culling those to the best 100 of them, that became the book.

OT: When you were looking back on all these letters and personal messages, did you think about how much different it would be if you received or composed these letters as you are now?

NDT: That happens on several levels. The first is, I could compose that sentence better than I could 10 or 20 years ago, so I reserve the right to clarify the sentences [laughs]. My letters are edited for clarity and the people’s letters are edited for length. Generally, I don’t reply to something unless I have researched the subject thoroughly. Often, they’re so well-researched that it’s not likely to be improved later on. I did a lot of research on religion. Why? Because people asked me about it, so I said I couldn’t reply unless I had some foundational knowledge on what the hell I’m talking about. If someone asks me about how God relates to science, I can’t just answer it from a scientific point of view. When you [ask], “Have I grown or evolved?” [the answer is], I evolve in the moment before I reply.

OT: You’re doing the book tour in a ton of places. Does it mean more to you to have these kinds of discussions in DC where national decisions get made by politicians?

NDT: Most public talks I give are not book-based. This little stretch is specific to the book. Generally, when I give talks in DC, my commentary that frames the content or the humor that I lean toward tends to be more DC-oriented. The flavor is definitely a DC flavor, knowing there will be movers and shakers there or an article could be written that could be read by a mover or shaker. Talks are not cookie-cutter in that sense. For example, one of the letters in the book rails against me for advocating for tax funding going toward NASA, so I might bring that up in DC. I might select letters more befitting to that region in the country.

OT: You’ve written several books in the past few years, and you’ve obviously had success with “Star Talk,” your visits on the longform “Joe Rogan Experience,” etc. Have you noticed an uptick in the hunger people have for science, and specifically astrophysics and theoretical physics?

NDT: I wonder if it’s not that the hunger is up, but it’s the ability to reveal that they’re hungry. How could The Big Bang Theory sitcom have been number one for so long? If you look at the list of long-running number one shows, it’s in the top few of that list. So, how did that happen? Where did that come from? I think I am on that landscape as someone who is sharing the joys of science with the public, and I’m delighted to recognize and report that there is a hunger out there. There’s a lot of ways to do it: videos, podcasts, etc.

OT: You’ve had a tremendous amount of success blending your knowledge with pop culture. Do you sometimes feel like you’re one of the first stops people make on their journey to looking into science?

NDT: That’s true, however, I would worry about it if I was the sole driver of this. Look at how many Twitter followers NASA has, or the Instagram followers Nat Geo has. Go look at the Facebook page I f–king love science [Ed. Note: we did, and over 25 million people like it]. Whatever role I’m playing in this landscape, no matter how large it is, there are larger things at play. It would be weird if I was the driving force. My goal is always to get people interested in science, and I’m happy to be a guide to the cosmos. But it’s the science, not the person.

See Neil deGrasse Tyson speak at Warner Theatre on October 23.

Discussion begins at 7:30 p.m., tickets $67.50.

For more about Letters from an Astrophysicist, visit www.haydenplanetarium.org/tyson or follow him on Twitter @neiltyson.

Warner Theatre: 513 13th St. NW, DC; 202-783-4000; www.warnertheatredc.com