Culture

Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum

Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum

Carnival and a Barking Dog: Rufino Tamayo at SAAM

March 2, 2018 @ 12:00am

David Alfaro Siqueiros famously said, “Our is the only way.”

Siqueiros was one of the “big three” Mexican muralists, alongside Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, and he sounds like he was a bit of a bully. The response of his contemporary Rufino Tamayo is excellent.

“Can you believe that, to say that ours is the only path when the fundamental thing in art is freedom? In art, there are millions of paths – as many paths as there are artists.”

Tamayo was another modernist from Mexico, and his path has nothing to do with the social realism of his contemporaries. His paintings are representational, but never mimetic. They’re more surreal and draw on the history of Mexican art, from Mesoamerican ceramics to Mexican popular art (the term for Mexican folk art).

His work is on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM)’s current exhibition, Tamayo: The New York Years. The exhibit charts his journey from his beginnings in Mexico in the 1920s to post-World War II, when his work defined Mexican modernism for many people, and it explores how his years in New York led him to that end.

E. Carmen Ramos, the exhibit curator, led me from piece to piece. She is deputy chief curator and curator of Latino art for the Smithsonian American Art Museum. She explained Tamayo first traveled to New York City when the dominant attitude of his contemporaries in Mexico became too strict. He was “bit by the New York bug,” Ramos told me, and would live there at various points throughout his career.

New York City was to Tamayo what Paris was to other modernists. He found a community of artist friends – he lived near 14 Street and developed relationships with artists including Reginald Marsh and Stuart Davis – and was exposed to international modernist art including de Chirico and Picasso.

![Rufino Tamayo, New York Seen from the Terrace [Nueva York desde la terraza], 1937, oil on canvas, 20 3/8 x 34 3/8 in. FEMSA Collection. © Tamayo Heirs/Mexico/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Roberto Ortiz](https://districtfray.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/tamayo_new_york_terrace-scaled.jpg)

Rufino Tamayo, New York Seen from the Terrace [Nueva York desde la terraza], 1937, oil on canvas, 20 3/8 x 343/8 in. FEMSA Collection. © Tamayo Heirs/Mexico/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Roberto Ortiz

The skyline he paints is of NYC, but it very much belongs to Tamayo. The use of color is fanciful, and he depicts a collection of different architectural landmarks alongside one another. The painting is also partial self-portrait – a representation of himself and Olga – and even part still life. This is a watermelon and refers to Mexico, and it pervades 19th-century Mexican still life paintings.

“When’s the last time you saw a red striped building?” Ramos asked as we looked at the painting. “Or a green sky for that matter?”

“It’s been too long,” I replied.

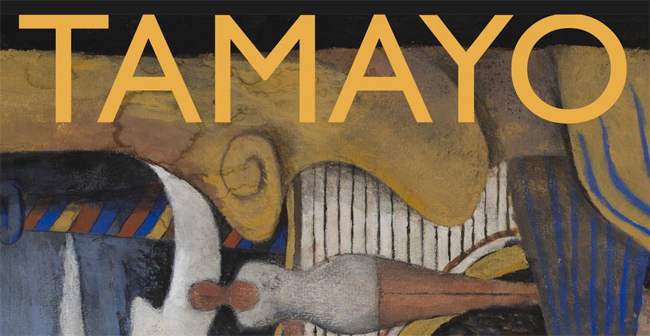

Tamayo encountered de Chirico on his first trip to the big apple in 1926. But it wasn’t until 1939 that Tamayo encountered Picasso, and the experience Picasso’s painting had on him was profound, as it was to so many other artists at the time. Upon seeing Picasso’s “Guernica” (1937), he drew inspiration, which emerged in his own “Carnaval” (1941).

“Carnaval” portrays a couple donning masks and otherwise preparing for carnival. In color and organization of form, the piece is stylized. Here, you can see how Picasso’s African period rekindles Tamayo’s affinity for Mesoamerican ceramic figures and Mexican popular art.

![Rufino Tamayo, Carnival [Carnaval], 1941, oil on canvas, 44 1/8 x 33 1/4 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1942. © Tamayo Heirs/Mexico/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.](https://districtfray.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/tamayo_carnival.jpg)

Rufino Tamayo, Carnival [Carnaval], 1941, oil on canvas, 44 1/8 x 33 1/4 in. The Phillips Collection,Washington, DC, Acquired 1942. © Tamayo Heirs/Mexico/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Ramos said that she emphasized researching the masks depicted in the painting, because the interpretation of the work may differ if the masks were associated with one festival or another. But she told me that she discovered the masks are a hybrid of several different masks from all over the country, including Jalisco and Mexico City.

The influence of “Guernica” is heavily brought to bear in “Dog Barking at the Moon” (1942). The former stirred intense discussion around art and propaganda; how artists should represent contemporary times and whether social realism is the best answer. “Guernica” became “very near and dear to Tamayo,” Ramos said, and given his differences with contemporaries, it’s easy to see how.

The painting portrays a black moon that looks tiny by comparison to the colossal and violently red dog. It is one of a series of animal paintings that to my Bauhaus and Der Blaue Reiter-steeped mind conjure up Franz Marc, but Ramos said otherwise.

“His most striking response to Picasso is a series of animal paintings,” she said. “They’re meant to engage the anxiety of World War II and the post-war moment. He was living in New York during World War II and these were very anxious times. He creates this body of work around these desperate, howling, aggressive animals that give a sense of [anxiety], that represent the war not photographically but more allegorically.”

![Rufino Tamayo, Dog Barking at the Moon [Perro ladrando a la luna], 1942, oil on canvas, 47 1/4 x 33 7/16 in. Private collection. © Tamayo Heirs/Mexico/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.](https://districtfray.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/tamayo-dog-barking-at-moon-scaled.jpg)

Rufino Tamayo, Dog Barking at the Moon [Perro ladrando a la luna], 1942, oil on canvas, 47 1/4 x 33 7/16 in.Private collection. © Tamayo Heirs/Mexico/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

“When I was reading [contemporaneous] reviews, it was not only the number of reviews, but there was one review I was reading that said he was a ‘fixed star’ [in New York],” Ramos told me. “Look Magazine did a survey of important artists and he pops up as one of the most important artists in New York, so he’s a figure.”

For more on Tamayo read his obituary in The New York Times. Tamayo: The New York Years is on display at SAAM through March 18. The exhibit is open to the public every day from 11:30 a.m. – 7 p.m. The exhibit is also wholly bilingual with panels in both English and Spanish.

Smithsonian American Art Museum: 8th and F Streets NW, DC; 202-633-1000; www.americanart.si.edu