Culture

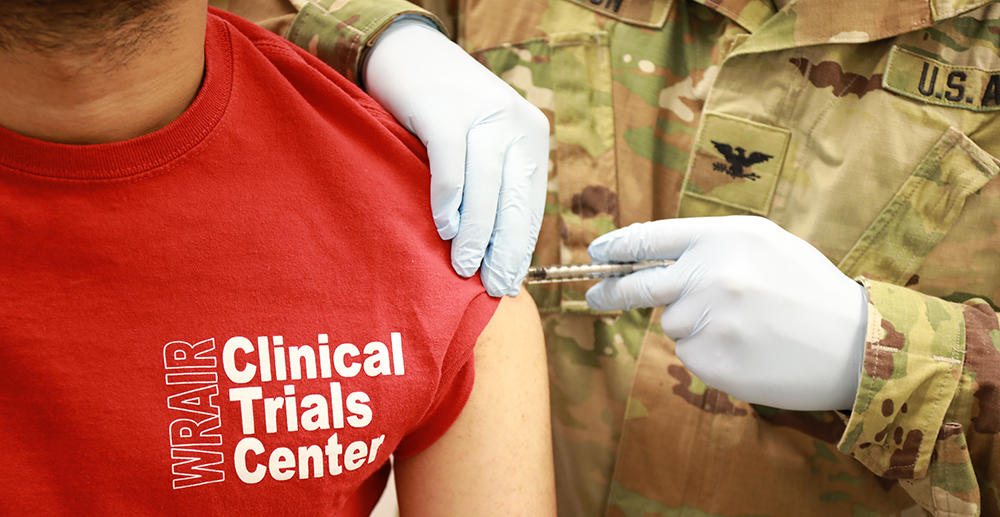

Photo: courtesy of WRAIR

Photo: courtesy of WRAIR

WRAIR’s Clinical Trials Helping To Cure the World

February 5, 2020 @ 12:00am

Clinical trials are necessary for discovering new treatments for diseases, as well as finding new ways to detect, diagnose and decrease the chance of developing a disease.

The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), located in Silver Spring, Maryland, regularly studies what are often referred to as, “neglected tropical diseases,” or diseases that cause significant illness among the world’s poorest populations as well as pose a health threat for U.S. military members traveling overseas. These include malaria, dengue, yellow fever, Ebola, leishmaniasis, as well as certain types of viral hepatitis, infectious diarrheas and meningitis, among others.

Like all clinical research in the U.S., studies at the WRAIR are conducted on human volunteers under very strict safety regulations to test if new drugs, vaccines or devices are safe and effective – and everything is first tested extensively in labs and preclinical safety testing, before testing is ever allowed on people.

Lt. Col. Melinda Hamer, MD, an emergency medical doctor by training, serves as director of WRAIR’s Clinical Trials Center (CTC) and has spent a significant portion of her career researching infectious diseases.

After stints with Johns Hopkins Emergency Medicine and Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, she was asked to join the WRAIR CTC in 2017.

“This is a unique place to be and there are really few places like it in the world,” she says. “In addition to discovering and manufacturing new vaccines and drugs, we are able to conduct clinical research to assess candidates that have the potential to combat some of the world’s most deadly pathogens. We like to say we address diseases from Anthrax to Zika.”

Although the U.S. Army and the WRAIR have a long history of conducting clinical trials, the CTC was formally established in 1992 to conduct these highly-regulated clinical trials to evaluate the safety of the vaccine products and learn if they actually work to fight these diseases.

“Our center has been involved in a number of different key milestones and breakthroughs in terms of new vaccines and new treatments,” Hamer says. “For example, there’s a disease called Japanese encephalitis virus, and our center did several significant clinical trials that helped pave the way for a product to be licensed to prevent this disease.”

That was important for U.S. soldiers who deploy to the Southeast Asia region, and the vaccine is also commercially available to help prevent the disease for those who live in areas where the virus is endemic – particularly children, who are more susceptible to death or permanent neurological problems from malaria.

Other examples include helping with several anti-malaria drugs, and all of the different ones used by U.S. soldiers today were touched in some way by researchers at WRAIR.

“More recently, with the Ebola outbreak in 2014-15, we were selected as the first site in the world to test the Ebola vaccine and that is now being used to stem the tide of the current outbreak,” Hamer says. “It’s the one that is being used in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and it appears to prevent folks from getting Ebola and spreading this terrible disease.”

In her role as director, Hamer is responsible for the safety of everyone who receives test vaccines and ensuring they are appropriate for participating in the clinical trials, as well as doing safety assessments during the trial. She leads a team of about two dozen clinical research professionals including three doctors and eight research coordinators, and she notes that success is really a team effort.

Hamer emphasizes that there is a tremendous amount of planning that goes on just to start a clinical trial.

“We are constantly having meetings with study sponsors and all the different people on staff who are participating in the trial – different clinical coordinators, experts making sure we are adhering to all the regulations, and then plotting out what phases we should focus on and what grant or funding proposals we should apply for next,” she says. “It’s really cool work and I’m here with a lot of really amazing scientists.”

Once a study is over, the data needs to be reported to the FDA and study findings published. It takes a lot of research and several different studies in human beings for a new vaccine or drug to be approved by the FDA and licensed. It can often take 10 years or more.

At any one time, 5-10 studies are being worked on at the WRAIR Clinical Trials Center, and some new ones are in the works for 2020. The CTC plans to be recruiting for these studies soon.

“For those interested, they should know that although there is always some risk associated with testing new products, each study is vetted thoroughly to see how we can make the study as safe as possible. There are quite a few essential safety studies in the laboratory, and in non-clinical safety evaluations that go on before any of these products are even thought about for testing in human beings,” Hamer says. “There are very strict regulations and product review that both the Army and the FDA require.”

The CTC is housed in what looks like a typical doctor’s office. There’s a waiting room, three exam rooms and labs where things are being studied.

For those who volunteer, Hamer explains the initial visit or “screening” visit will have study personnel collecting information about a volunteer’s medical history and any medications or specific criteria that will determine if one is eligible to participate in a particular study. Typically a brief physical exam is also involved. If volunteers are eligible for the study, a vaccination or medication dosing visit will generally be the first official study visit. At that visit volunteers will be briefly checked by a doctor to make sure they are doing ok and are healthy and to confirm their continued willingness to participate, and if so, they will get the first shot or dose of medication. After they receive the dose, someone will watch them for thirty to sixty minutes, and then they will be reassessed before allowed to leave.

Throughout the study, volunteers may be asked to come in for evaluations including blood tests so researchers can look at the volunteer’s immune response, or antibodies, to make sure they are producing the right response to potential infection, and to ensure there are no abnormalities are going on. Antibodies, as many may know, are Y-shaped proteins in the blood to help stop intruders – such as bacteria and viruses – from harming the body. Other safety checks, such as regular blood tests and questions about any doctor visits or medication changes, are also performed at the study visits to ensure that volunteers have had no problems or concerns associated with any of the research products.

Volunteers are compensated since it requires a commitment to participate, and those who want to become part of it also need to be serious about their involvement. Although volunteers have the right to leave a study at any time, Hamer says it’s a little bit like a job in that people will have scheduled times they need to come in and they may have other obligations associated with it.

Studies can last anywhere from 2-3 months to 18 months or longer, but the majority fall in the 10-month to a year range. A recent study involved eight total visits by participants, but some require more.

“We get a lot of repeat volunteers. Once they understand what it is and what we do, many will come back and even invite family and friends to participate,” Hamer says. “We see people in our clinic starting at 6 a.m., so a lot of folks will just come before work and we can accommodate work schedules.”

Hamer is proud of her work and believes that the research is extremely important, and is thankful for all the scientists and volunteers who are involved.

“It’s incredible to think about that we’re coming up with potential solutions for some of the world’s most challenging and terrible diseases,” she says.

For more information on current studies or upcoming ones seeing volunteers, visit here.