Life

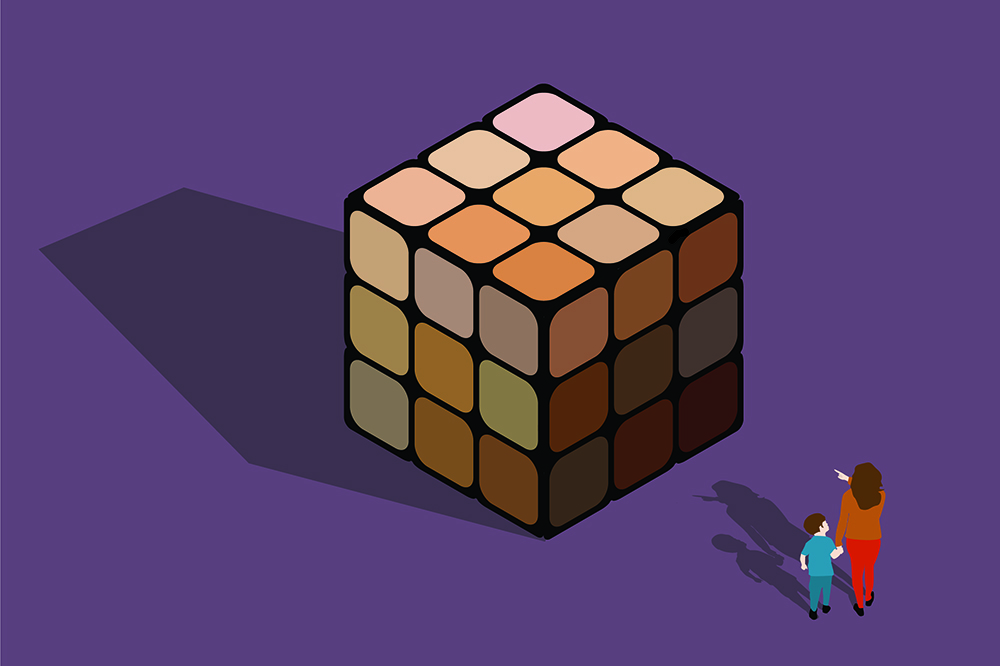

Illustration by James Coreas.

Illustration by James Coreas.

Learning to Raise an Ally

July 10, 2020 @ 10:00am

I found out I was pregnant with my first child during the winter of 2019, and almost immediately, I learned how much people cared about the baby’s biological sex. At the time, I felt secretive about this information. I didn’t want people’s ideas about gender to shape or limit my child in any way. My husband and I discussed early on how we would embrace our son’s identity – whatever it is – and counter the external, cultural pressures he might feel about what it means to be a boy and masculine.

I have always loved children’s books, so even before my son was born, I began curating a library that featured strong girls, boys who aren’t traditionally masculine, and racially and ethnically diverse characters. We had a plan: We would use books and toys to celebrate all the ways people are different, encourage our son to embrace and be curious about those differences, and answer his questions truthfully and in age-appropriate language.

Amid the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in the past few months, I began to consider the ways in which our approach would be insufficient. I am prepared to talk to my child about the importance of diversity, equity and inclusion. But I am not equipped to talk to my son about racism in America and our role – his role – in fighting against it.

Understanding Our Children’s Identities

The first thing to recognize as parents of white children is that we are privileged to have the option to talk about race and learn about racism rather than experience it. In a Washington Post article published last month, Khama Ennis, a Black woman and chief of emergency medicine at a Massachusetts hospital, describes talking to her daughters about racism at ages 5 and 7.

“They had to learn to recognize hatred if there was any hope of them being able to call it out, name it and most importantly, know it was wrong,” Ennis says in the June 5 piece. “It was a painful conversation that they still remember.”

While Black families face the horrific necessity of talking to their children about anti-Black racism in America, white families tend to avoid talking about race altogether. Our children won’t experience racism, so why talk about race?

Even if we do not hold racist values, if we are not actively fighting against racism then we are complicit in all the ways that it happens around us every day – whether we notice it or not. If I want to raise my son to be anti-racist, teaching him to be kind and embrace differences isn’t enough.

It’s easy to teach our children how the world should be. Although more difficult, we must also teach our children about discrimination and violence in America, why they exist, and how we can and must actively fight against the beliefs and systems that perpetuate inequity.

Many parents worry that talking to their child about race will make their child racist – that drawing attention to our differences will lead to prejudice. Numerous studies show that, in fact, the opposite is true.

Pediatric psychologist Dr. Ann-Louise Lockhart explained in a recent webinar panel that, “As early as 6 months of age, babies notice racial differences. By 3 or 4, if they’re not told, educated and guided, they will start to develop racial bias.”

We all have conscious and unconscious biases. It is human nature to find patterns, make judgments and categorize the world around us. But being aware of both our personal and cultural biases is critical. We encounter prejudices every day, and if we don’t constantly recognize and correct them, they become our own. Without any action on my part, my son will learn harmful stereotypes and ideologies about women, the LGBTQ community and people of color. I can’t shield him from these ideas, but I can ensure that he doesn’t believe them.

Lawyer, professor and critical race theory scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality describes how individuals have distinct identities that intersect in ways that impact how they are viewed, understood and treated.

We all worry about the safety and well-being of our children, but my fears as the parent of a white son are distinctly different than those of parents with daughters or Black children.

Ennis describes how “the parents of Black sons in particular have to spell out, in excruciating detail, what to do if and when they have an encounter with law enforcement.”

The conversations in our household will certainly be different, but they are still necessary. Discussing our identities requires an awareness of the ways in which some are oppressed and under-resourced, some hold power and privilege, and some experience both.

So how will I talk to my son about his race? How will I teach him confidence and self-love while simultaneously teaching him about the enslavement, exploitation and marginalization of Black people in America? The point here isn’t to make him feel guilty or ashamed of being white or male.

But it’s important for him to recognize the ways that this country was built for us – and not others – to thrive. Recognizing all the ways we hold privilege and understanding our identities and how they determine our role in society helps us to see where we have agency. We can develop courage and learn to be allies and advocates. We don’t have to be silent or complicit – and so we won’t.

How To Begin

The work of raising anti-racist kids can begin even before they can talk. Lockhart encourages parents to represent BIPOC (Black, indigenous and people of color) authors, characters and artists into their child’s life as early as infancy.

“Seeing a person of color in a book or cartoon shouldn’t be strange or abnormal,” she says. “It should be part of everyday life.”

This is especially important for families whose communities are predominantly white. Evaluate the ways in which you intentionally or subconsciously surround your family with other white people and consider how you can reset your own biases. For your child, normalizing diversity early can help to prevent racial bias.

When our children do begin to talk, we can prepare to answer their questions and talk openly about race. Dr. Caryn Park, professor at the School of Education at Antioch University Seattle, describes the hypothetical scenario of a white child seeing a Black person in public. The child might observe to her parent that she has noticed that the person looks different, even if there is no value judgement. The child will then “look to the adults for a cue […] to track how my adult is responding to this observation I have made,” Park says in the aforementioned webinar panel with Lockhart.

When adults respond with panic or embarrassment, Park describes how the child’s first moment of observation is now associated with the idea that it’s not okay to talk about race and furthermore, it’s not okay to notice when people are different. By avoiding a conversation, you ensure not that your child will be unaware of race but rather, they will learn about it from the world around us instead of from you. In a recent interview, Jennifer Harvey, author of Raising White Kids: Bringing Up Children in a Racially Unjust America, draws a parallel to sex: Kids will learn and be curious about sex whether we’re ready or not. Would we rather they be left to their own devices or talk to us, their parents?

If you don’t know how to start a conversation, Park suggests asking your child, “What do you think about this difference?” and teaching from there. If your child is in a situation where they are the minority, notice if they feel uncomfortable and be willing to talk about it. In situations where they are the majority, remind them what it feels like to be different, and encourage them to be welcoming of kids who might be in the minority and speak up when other kids are unkind. Conversations might feel awkward, silly or obvious, but they can have a significant impact. One study from 2011 found that 5- to 7-year-old white kids who discussed race with their parents for one week showed less racial bias than kids who didn’t.

The question of when and how to talk about what depends on the child. Their age, personality and development are all factors. But by setting a precedent that it’s important to talk about complex, sensitive topics and ensuring they know early in life that it’s okay to ask and you’re ready to engage with them, you can follow their lead and be prepared to respond to questions as they arise.

Join Me

I’m sharing my story not as an expert, but as an imperfect human and new mom who cares deeply about raising a generation that is more kind, compassionate and anti-racist than my own. Of course, to be good teachers, we must first educate ourselves. The journey of raising anti-racist children is ongoing, and while it starts with our own reeducation, we don’t need to be perfect to begin. By teaching our children about identity, celebrating diversity, talking to them openly and encouraging them to call out hate when they see it, we can start to make positive change in our communities.

Being an adult in a child’s life is both a responsibility and an opportunity. We all have much to learn and as parents – especially new ones – we might feel lost, overwhelmed or unqualified. Protecting our children is hard enough without also teaching them how to make the world a better place. But I’m going to try to do both, and I invite you to join me.

9 Bite-Sized Resources

1. 13th // Netflix documentary

2. The Conscious Kid // Parenting + education through a critical race lens // On Instagram @theconsciouskid

3. Curious Parenting // A community for caregivers of all kinds interested in raising resilient, liberated kids // On Instagram @curious.parenting

4. “The Difference Between Being ‘Not Racist’ and Anti-Racist” // TED Talk by Ibram X. Kendi

5. EmbraceRace // An organization focused on supporting racial justice for all children // www.embracerace.org

6. “Raising White Kids with Jennifer Harvey”// Aired May 21, 2020 on the Integrated Schools podcast

7. This Book Is Anti-Racist: 20 Lessons on How to Wake Up, Take Action, and Do the Work by Tiffany Jewell

8. “The Urgency of Intersectionality” // TED Talk by Kimberlé Crenshaw

9. White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo

Claire Smalley is an art director and graphic designer living in Northern Virginia.

Enjoy this piece? Consider becoming a member for access to our premium digital content and to get a monthly print edition delivered to your door. Support local journalism and start your membership today.