Culture

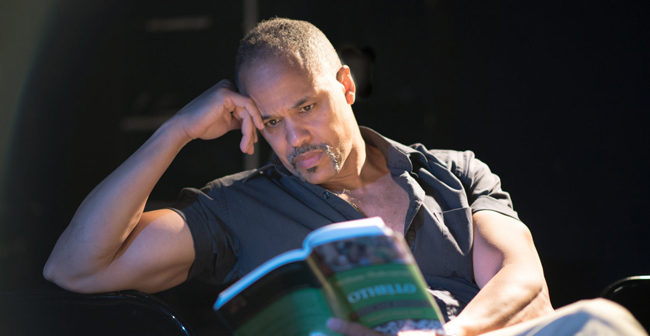

Photo: Chris Lang

Photo: Chris Lang

American Moor Sheds Light on Black Experience

January 8, 2019 @ 12:00am

After a devastating break-in over the holidays, the Anacostia Playhouse is bouncing back and happily welcoming playwright and actor Keith Hamilton Cobbs for his work American Moor from January 9 to February 3. Considered a significant play by the Folger Shakespeare Library, American Moor uses Shakespearean character Othello as a lens to examine the experiences and perspectives of diverse Americans. With television and film credits dating back 20 years including The Young and The Restless, All My Children and CSI: Miami, to name a few, Cobbs has a perspective that resonates. We caught up with him about his role in American Moor before the run begins this week.

On Tap: What is life like after two decades of acting in notable TV roles?

Keith Hamilton Cobbs: Well, life is the same except there’s not as much money in it [laughs]. The last [soap opera] I did ended in 2003, so there has been quite a space in-between. I have been writing and producing [American Moor] for the last seven years. It’s the life of any artist who is not necessarily the object of popular culture. For the object of popular culture, there’s a lot of work, tension and money. For the other artist, they’re just out there making art and living their everyday lives – and my life is a bit like that. I haven’t changed. I am the same, whether I’m the guy doing the soap opera or the guy you’re talking to. I am older, right? But life goes on. You start being an older actor and dealing with all the things older actors deal with.

OT: What story are you trying to tell with American Moor?

KHC: The story of humans, but certainly as Americans. It talks about our particular American dilemma with race, with biases and otherness with making art.

OT: Where did you draw inspiration from for this play?

KHC: This piece started out as an expression of my experience as an African-American actor trying to forge a career and how that related to my reality as an African-American man trying to shape a life. I realized at some point they were the same thing, and that realization created the first draft of the play. But something really profound and glorious happened. When we started to show the play and have post-production discussions, people started to get up and speak back to the play – relaying their experiences and reactions to the play. We realized the cross section of people who were speaking was extremely broad and diverse. Here I am, telling this story about me and my life, but they’re seeing themselves and their lives.

OT: How do you imagine the outcome of expanding narratives across all spectrums?

KHC: What my play is trying to suggest is here you have this person standing in front of you, and if you could expand your frame just a little bit, you’d see you were being offered something. You’re being offered perspective. You’re being offered authenticity. You’re being offered intellect. You’re being offered diligence in the form of this actor. You are being offered all these wonderful things that go into making wonderful theatre, and you are afraid to see them because they threaten what is for you. Were all of us not to be afraid, everything would change. We would begin to explore and discover all sorts of things about one another, certainly about art. Art would expand exponentially into what it would show of us, how it would represent us and what it could teach us.

OT: You portray an actor auditioning for the role of Othello, and you confront a director who expects you to fit into a narrow perspective of what an African American playing this role should be. Has this happened to you often in your career?

KHC: Yes, it has happened several times in terms of reading for the character Othello or being considered in relation to that character. People would say, “Oh, you would make a great Othello,” and that’s like someone saying, “You would make a great basketball player.” Well, why? You don’t know anything about me. How do you know I would make a great Othello? All you know is what you are looking at. So yes, that has happened several times. But it has also happened in my life as a black American. As African males, we are seen in a particular way. Certain assumptions are going to be made about us walking in the room.

OT: Where do you believe the root cause of the problem lies?

KHC: It is ownership of the American narrative. Who owns the narrative? It is still the property of white male Americans – European descendants. The story is theirs. It is about them. The rules are about them, it is skewed toward them. [It] favors them, and they’re going to say what works and what doesn’t. That extends to ownership of theatre. We take most of our theatre that we perceive as good and important from the white Western canon of work, Shakespeare included.

OT: How have the reactions of your diverse audiences impacted your script?

KHC: The work of rewriting this piece – honing and making this dramatic art more efficient – was already being done. But as I began to understand that this piece was about more than me, it allowed me to write in a direction that made the point clearer. This is everyone’s story.

OT: What distinction do you make between typecasting within the African-American male experience and other races or genders?

KHC: It’s an issue for everyone. I’m not making a distinction. As I say, the play is about all of us. It is about racial othering, sexual othering, othering by age. Othering is othering. It crosses all life spectrums. A little less than a year after writing the first draft – [after] the first public performance of this very raw new piece – the responses were from people, who in any simple comparison, were very much unlike me.

OT: How so?

KHC: Well, there was a little Jewish high school girl who got up and said, “That’s my story. This is me. This is the life I live.” I thought, oh my goodness! Wow, alright! Well, let me look at that. Let me hear you. Let me examine. I began to listen very closely to what people had to say about their experience of this work. It expanded my thoughts and my mind. I realized this wasn’t so much about me, but about the experience of all of us. When you see the play, I feel it’s safe to say you will see yourself on some level.

OT: What’s are the consequences of limitation for character portrayals?

KHC: The consequences are that we don’t grow. As a culture, we do not evolve and we sit in what is comfortable. We sit in what we can define because it is comfortable. We fear change. We shun change and growth and deeper exploration of one another. We will not consider and explore other people’s ideas because so much of what we live now – so much of white male privilege – is based on what exists right now. If it changes, white male privilege becomes threatened.

OT: Why did you choose Shakespeare as the lens through which to tell this story? How did you get into Shakespeare?

KHC: I was studying English and realized when I started to see Shakespeare performed [that] the characters were able to express a depth of emotions as characters in a play that I as a black man was not able to express. The depth of my emotions was something people perceived as dangerous, which I could be shot for. Those characters would open their mouths and say the most beautiful things and express whatever emotions they wanted to express. I decided that I wanted to do that. This gives me a place where I can put all of these emotions.

OT: What impact do you hope American Moor has on American culture?

KHC: It’s already had impact, generating deep thought and conversation about these issues of race – whose perspectives matter, whose art matters – [and] about the nature of love and the declining qualitative nature of our American theatre. How do we fix that?

OT: How do you propose we fix this problem?

KHC: You start with awareness. You start with realizing it is broken. You start with the admission that it’s being made for many of the wrong reasons. You begin to try to think outside of your boxes of privileged perspective. You demand that your educational institutions training actors [and] directors do better and instill in them values that are appropriate to what theatre is supposed to do. These are big things that require individuals to take responsibility as individuals. Discern the truth, because you are the purveyors of truth.

American Moor opens Wednesday, January 9 at the Anacostia Playhouse. Tickets are $30-$40. For more information, click here.

Anacostia Playhouse: 2020 Shannon Pl. SE, DC; 202-290-2328; www.anacostiaplayhouse.com